History

It all began with friendship

Saginaw became a sister city with Tokushima, Japan in 1961. The initiative was spawned by Hiroyuki Takagi from Tokushima, a young exchange student at Michigan State University, who lived in Saginaw while pursuing his field of study. When Hiroyuki returned home, he took with him a dream and enthusiasm to form a relationship between the two cities.

When Hiroyuki approached the mayor of Tokushima with his idea, he was met with a question: “Why Saginaw? Why not a well-known American city, like New York or Los Angeles?” Hiroyuki’s response was simple: “The people of Saginaw may ask, ‘Why Tokushima?'” It was his persistence, sincerity, and support from his Saginaw host family that finally made his vision come true on August 24th, 1961 marking the start of a lasting relationship between the two cities.

Creating an urban oasis:

The Saginaw-Tokushima Friendship Garden has provided a serene sanctuary for over 50 years

As a reminder of a tangible friendship between the two cities, the Saginaw city council dedicated a property to the cause in 1963 and spent the next five years planning and fundraising to create the garden.

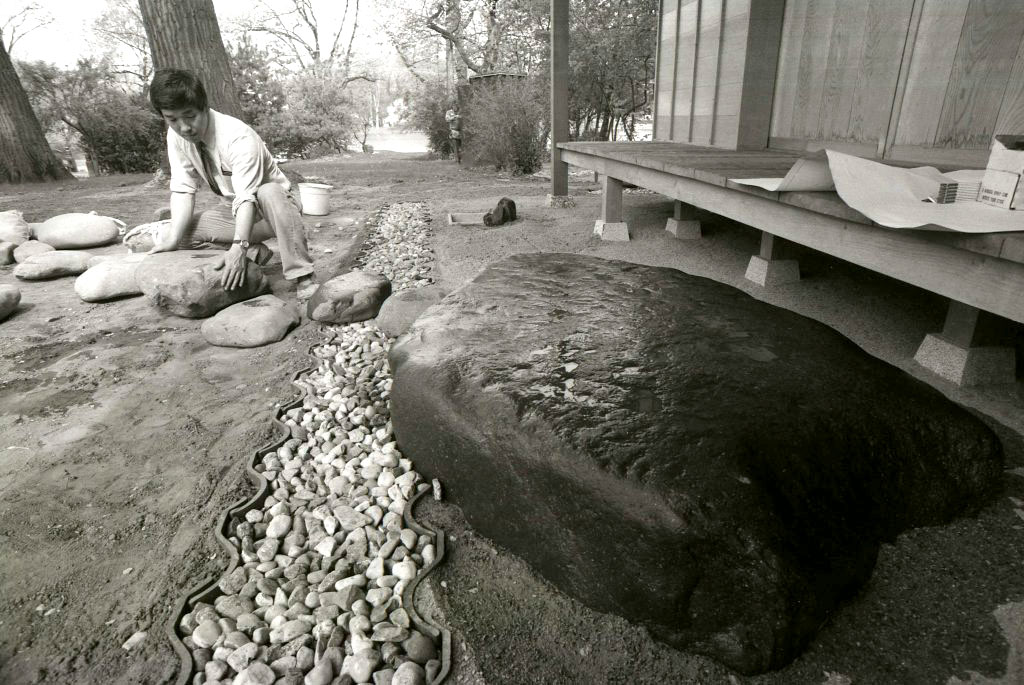

The City of Tokushima sent two stone lanterns, in addition to their greatest contribution, and the landscape artist, Yataro Suzue. With 45 years of professional experience, the 68-year-old took over working operations together with Lori Barber, a Saginaw native, garden designer. He spent 80 days in Saginaw overseeing the construction, which included the placement of literally every rock, some weighing up to four tons. Mr. Suzue also donated several boulders excavated from Tokushima’s Anabuki River, prized for their unique bluish-green color. “All I want to do is to recreate beauty. God made nature, but gave people the power to create the art that constitutes it” he stated.

“Beauty is not trickery, not illusion…but arranging elements like trees, water, and rocks in a way that there is no crowding, no competition for attention.” (Yataro Suzue, Tokushima’s native landscape artist, 1971.)

Nestled in the garden—Awa Saginaw An

On August 7, 1978, the Saginaw City Council gifted half of the garden property, measuring 18,000 square feet, to Tokushima as a symbol of friendship. It was hoped that one day an authentic Japanese teahouse would be built, with half belonging to Saginaw and the other half to Tokushima. The cost of construction as well as labor was divided equally between both cities.

Tsutomu Takenaka, the teahouse architect of Sen Art Studio in Kyoto, along with city planning officials from Tokushima, visited Saginaw in 1980 to draw up blueprints for the teahouse. However, due to economic hardships in those years, fundraising proved to be challenging. After years of persistence, the two cities finally reached their funding goal in November 1984.

Master carpenters trained in the centuries-old art of Japanese joinery crafted and assembled the inside framework of the tearoom in Japan without using nails, screws, or power tools. Each piece of wood was carefully chosen for its quality and natural texture and then intricately notched and fitted together by hand.

After the framework was completed, it was disassembled and brought to Michigan, where Japanese craftsmen worked alongside American workers to reassemble it inside the pre-existing shell and on the foundation. The project took one year to complete, resulting in a beautiful teahouse built through the collaborative efforts of American and Japanese carpenters.

Jihei Takeuchi, a master Japanese carpenter from Kyoto, left an impression on his American counterparts. Trained as a sukiya daiku, an expert in centuries-old teahouse construction methods, he made little noise working with his traditional tools. Instead of power tools, the sukiya daiku shaped wood with nomi, a set of incredibly sharp chisels. Insisting that harsh rubbing would “kill” the natural grain of wood, Takeuchi would not use sandpaper. Instead, he used a kan-na, a plane made from a block of wood and a sharp piece of metal. In place of nails, wooden pegs were used to join pieces of wood in incredibly intricate patterns. No paint or varnish was used because it would mask the natural beauty of the wood. How sturdy could a structure built without modern equipment be? Jihei Takeuchi guaranteed his work to last “for 300 years.”

In addition to deploying Japanese specialists, the construction of the teahouse utilized materials imported from Japan to make it truly authentic. Building materials used to construct the teahouse convey humility and harmony with nature. The designer envisioned the structure to be simple and humble. In order to achieve this aesthetic effect, for example, knots in the wood as well as pieces of bark were left untouched. From the Kitayama Mountain of Kyoto came the finest Japanese cypress. Mud processed and shipped from Shikoku Island plastered the walls. Traditional Japanese tatami flooring made of woven straw covered the tearoom, and shoji, paper screens, filtered the light from the windows. Even the stepping-stones were carefully chosen in Japan and brought here. Mr. Takenaka would have accepted nothing but the best. If the building materials were off by an eighth of an inch or if the wood looked too dark or too light, work would stop until suitable replacements were found. Takenaka reached into his own pockets to cover extra expenses. “If I created an inferior-quality structure, Americans would say, ‘so, this is an example of Japanese standards.’ I don’t want that to happen. I want to show the best.”

Roji—a gateway to the world of tea ceremony

The tea ceremony experience begins with guests passing through a bamboo gate called Nakamon, which is intentionally narrow to discourage conversation. The path through the garden, roji, is made up of stepping-stones over mossy ground, and guests are encouraged to focus their attention on the present moment as they step from stone to stone.

The path leads to a stone water basin called Tsukubai, where a bamboo ladle is used to collect water from a bamboo spout known as kakei or kakehi. Rinsing hands and mouth at the Tsukubai represents purification, washing away mundane concerns and clearing the mind. The chaniwa tea garden features evergreens and shrubs, symbolizing the longevity and wisdom of old age revered in Zen, rather than flowering plants, as is common in most Japanese gardens since the 12th century.

The Roji culminates in the kutsunugi-ishi, a stone used for removing shoes before entering the teahouse. This stone is selected with great care to suit its intended purpose. The kutsunugi-ishi at Awa Saginaw An weighs more than 5000 pounds and, like all the other stepping stones in the roji, was imported from Japan.

The guests, upon their entry to the teahouse, proceed directly to the tokonoma alcove. The size of the alcove is equivalent to one tatami mat, and it displays objects for the guests to view. While the arrangement may vary, the customary objects placed in a tearoom’s tokonoma include a hanging scroll, a flower vase, and art objects. The left-hand column of the tokonoma, known as the toko-bashira pillar, is considered the most important aspect of the alcove since its form influences the character of the room. A guest kneels in front of the tokonoma, bows as a sign of appreciation and respect for the host’s thoughtfulness, and proceeds to admire and view the objects on display for their enjoyment.

Modern Tearoom – Ryurei Style

The Awa-Saginaw An not only has a traditional tatami mat tearoom but also an adjoining Ryurei-style room. This style was first introduced by the eleventh Grand Tea Master Gengensai for the 1873 exhibition in Tokyo. It deviated from the traditional style by using benches and tables, along with a stand for the tea utensils. The purpose of this adaptation was to accommodate Westerners who were not used to sitting on tatami mats. Although Gengensai’s innovation was met with criticism from the traditionalists of the tea ceremony school, it demonstrated his sincere desire to share the chanoyu experience with the world while preserving its authenticity for the Japanese.

Japanese Cultural Center, Tea House, and Gardens

527 Ezra Rust Drive

Saginaw, Michigan 48601

Phone: 989.759.1648

director@japaneseculturalcenter.org